Strong school leaders are stepping forward in increasing numbers to request more school-level control over their campus budgets, time, and focus. How could Denver’s systems and structures better support school leaders as the catalysts for positive change? What are the prerequisites for successful autonomy? How do we prepare a pipeline of educators to lead autonomous schools and networks? Where are the “break the mold” school models? How do we increase racial, ethnic, and gender diversity among our education leaders?

Moderator: Brett Alessi, Co-Founder & Managing Partner, Empower Schools

Panelists:

- Brandi Chin, Founding School Director, DSST Middle School @ Noel Campus

- Christine DeLeon, Founder, Moonshot edVentures

- Kurt Dennis, Principal, McAuliffe International School, DPS

- Scott Wolf, Principal, North High School, DPS

SESSION SUMMARY

Realizing Autonomy, Embracing Diversity Remain Challenges

By Alan Gottlieb, Write.Edit.Think.

Even in an environment like Denver that empowers principals, strong leaders are continually pushing their systems to gain more autonomy over more areas of their operation.

That was the consensus of principals from all types of schools — traditional district-run, innovation, and charter — on the “Empowering School Leaders” panel at the “Schools as the Unit of Change” convening.

Participants also agreed that more freedom should lead not only to better outcomes for kids, but also to greater community engagement. That means doing everything possible to make sure that the staff reflects the community it’s serving.

Kurt Dennis, executive principal of Denver’s McAuliffe International School, which now spans two campuses, said his school’s innovation school status provides significant freedoms to address specific community needs. But he believes creating an innovation zone will take that autonomy to another level.

“We have flexibility currently over budget, curriculum, staffing, and time. The next logical step in our progression would be around governance autonomy and using that to better serve students, staff, and community. That is what we are aspiring to,” Dennis said. That lack of governance autonomy has been a point of frustration for Dennis in recent years.

Dennis cautioned, however, that granting schools freedom without first having the right building leadership in place would be a mistake. “Handing just anyone a lot of autonomy without checks and balances in place is a dangerous thing,” he said.

Across town at North High School, Principal Scott Wolf has felt empowered without seeking innovation status or to become part of an innovation zone. He said he has a trusting relationship with his immediate superior, and is given plenty of freedom to “say no to things” as he sees fit.

The more he learns about the budgetary and hiring freedoms being granted to innovation schools and zones, however, the more interested he becomes in seeking greater autonomy, Wolf said.

And when he sees the freedom the charter school with which he shares his campus has to hire excellent teachers who have not gone through a traditional preparation program, the more he longs for that freedom as well.

Finally, Wolf said, the district needs to expedite the process of allowing any given school to decide which district services it wants, rather than being charged even for supports it doesn’t use.

Successful charter school networks like DSST Public Schools operate on a different, tight-loose replication model. Brandi Chin, who will be running the new DSST Middle School @ Noel starting this fall – the network’s eighth Denver campus — said she can adapt some aspects of her program to her community, which has a high rate of poverty and consists of almost all students of color.

“There is a balance and a tension,” Chin said. “Because DSST has been successful, there is a desire to replicate the model. But because each community is unique, with differing needs and strengths, there is room for autonomy as well.

“So far I am really happy with the balance. I get a lot of say in what we get to do and how we get to do it, and I get to bring a ton of ideas,” she said.

Echoing Kurt Dennis, Chin stressed that not every school leader is ready for full freedom. “It could be dangerous if we think it is just about putting people in a leadership position and telling them to go. Some of them aren’t ready,” she said.

Where charter networks and the district alike face struggles, however, is in recruiting a sufficient number of school leaders of color. New efforts underway show signs of helping change that, but there is still a long way to go. And, panelists said, until school leaders and staff more closely resemble the communities in which they work, deep community engagement will remain a challenge.

As a school leader of color, Chin is better positioned to serve the Far Northeast Denver community than many white leaders might be. But as a general rule. School systems have been slow to be aggressive in recruitment of teachers and leaders of color.

Christine DeLeon, the fourth panelist, founded an organization, Moonshot edVentures, to change that dynamic by building a pipeline of diverse leaders to run full-scale schools, micro-schools and other educational programs.

Changing the power dynamic and inviting diverse communities into school decision-making processes is an ongoing struggle, DeLeon said.

“All of us, not just the white people in the room, have to be comfortable with being really fearful and uncomfortable that we don’t get to dictate what happens all the time,” she said. “Losing that control, whether it is in a classroom or a school, or at a system level, is scary. We need to figure out how we become OK with that.”

Back to ‘Schools as the Unit of Change: Building on Progress in Denver’

Finally, also in 2023 a total of $410,956 previously committed by Gates to the

Finally, also in 2023 a total of $410,956 previously committed by Gates to the

A total of $1,110,956 committed to the

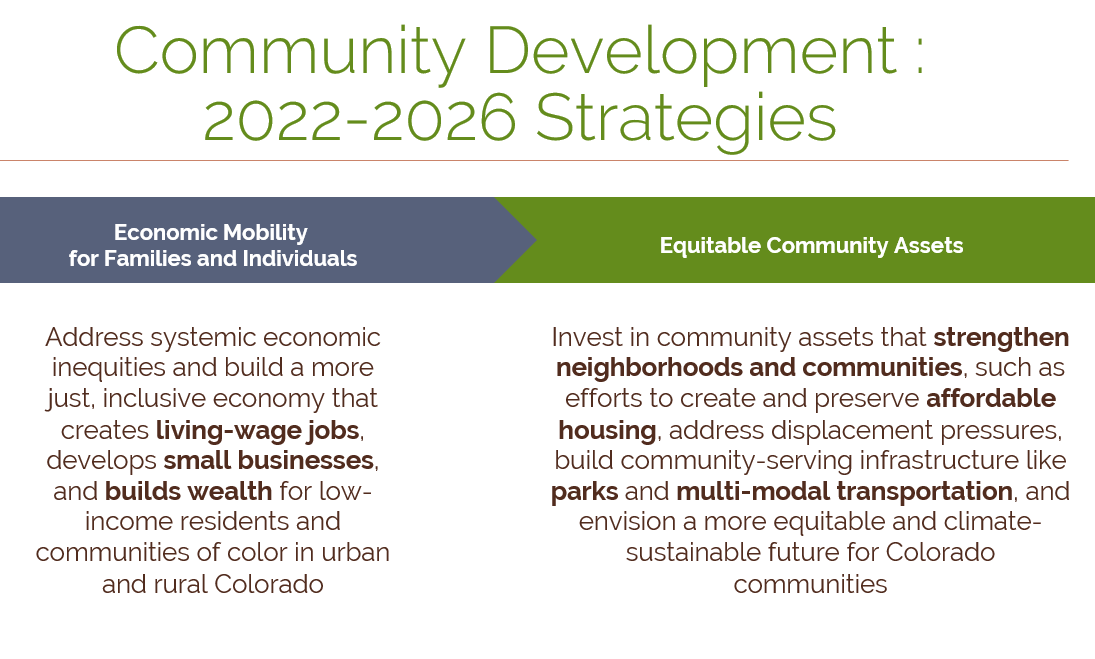

A total of $1,110,956 committed to the  In 2019, the Community Development program committed $932,500 in strategic grants to 13 organizations and $465,000 in responsive capital grants to 12 organizations. New impact investments supporting vibrant communities in 2019 included a $500,000 MRI to

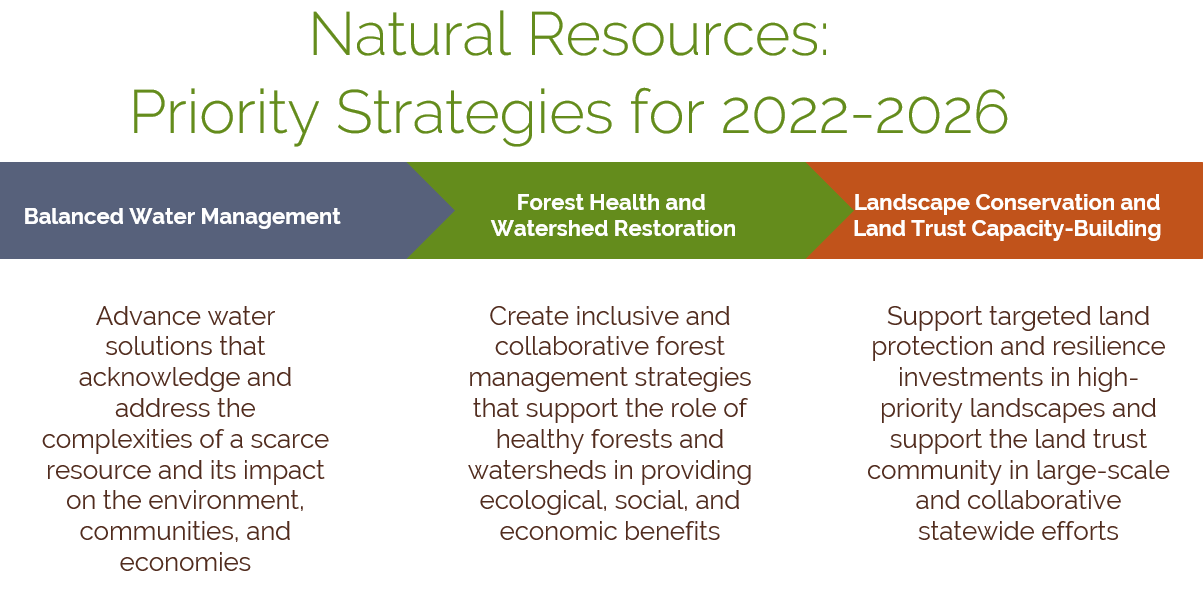

In 2019, the Community Development program committed $932,500 in strategic grants to 13 organizations and $465,000 in responsive capital grants to 12 organizations. New impact investments supporting vibrant communities in 2019 included a $500,000 MRI to  Our Focus Landscapes initiative, a key element of our Natural Resources program, underwent a comprehensive review, revision, and re-launch in 2019. This initiative was launched in 2011 to help Colorado achieve landscape-scale conservation through the protection of private lands in specific geographies. A great deal of progress was made in North Park, southeast Colorado, and the San Luis Valley, resulting in more than 200,000 acres of farm and ranch lands conserved, along with their associated ecological values. The strategic review process was done in close partnership with the land trust organizations representing those geographies, providing lessons-learned and an exploration of emerging opportunities. The revised Focus Landscapes initiative will first focus on two geographies:

Our Focus Landscapes initiative, a key element of our Natural Resources program, underwent a comprehensive review, revision, and re-launch in 2019. This initiative was launched in 2011 to help Colorado achieve landscape-scale conservation through the protection of private lands in specific geographies. A great deal of progress was made in North Park, southeast Colorado, and the San Luis Valley, resulting in more than 200,000 acres of farm and ranch lands conserved, along with their associated ecological values. The strategic review process was done in close partnership with the land trust organizations representing those geographies, providing lessons-learned and an exploration of emerging opportunities. The revised Focus Landscapes initiative will first focus on two geographies: