In January 2021, Richard Gates Kiely became the fourth member of the Gates family’s fourth generation to be elected to the Gates Family Foundation board of trustees. Not long after, and in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, Rich sat down with Melissa Davis, Vice President of Strategic Communications and Informed Communities, for a conversation that ranged from the past to present, and from founding intent to legacy.

Your father Rich was a Gates Family Foundation trustee for 12 years. What did you learn from him over the years – and from your mother, Sam – about philanthropy in general, and the Foundation’s role in Colorado specifically?

As a member of the Gates family, I’ve been given tremendous opportunities that a normal person just doesn’t get. There is a spirit within the family of being humble and making your own way, but also giving back and serving the family and the community both directly and indirectly. What I’ve learned from my parents and the Gates family – there is an unwritten assumption that you’re going to give back more than you’ve received. We need to use the opportunity that this family – back to my great-grandparents – provided to give back and do something meaningful. They succeeded in business and provided for family as a whole – so the expectation is that we won’t squander these opportunities. That’s the overarching thing that motivates me.

A big theme in the world of family philanthropy is “legacy.” Has your role as a trust and estate lawyer with Holland & Hart influenced or impacted the way you think about legacy?

Well, I’m on the litigation side of things, not planning – so I’m getting involved if there’s a dispute over what’s happened. So that certainly influences the way I think about the Foundation, whether it’s a specific grant or strategic planning for the next five years. At the end of the day, our purpose is to help the community – but within the bounds and intentions of my great-grandparents. I was born in 1984 and have no personal recollections of them. So our goal is to do the most and best with what we’ve been given, while also trying to stay true to their intent. That can be a challenge – and Tom has mentioned this – because it’s not like there was a specific issue they were dying to go into. I’m an analytical thinker – so I try to take my personal bias out of the decisions and go with what is consistent with the goals of the Foundation. At a very high level, that’s helping Colorado. But getting down to the more specific, that is where we as trustees and the next generation certainly have some discretion to make decisions and shape the Foundation going forward. But in my mind, it’s always driven by the fundamental goal of helping Colorado.

You worked for a while as a certified flight instructor, and have a B.S. in aeronautical management – what appealed (or appeals) to you about being a pilot? Do you still fly, and what role does flight play in your life now?

I’ve always been interested in flying and aviation since I was a little kid. My dad is a pilot, so I remember going flying with him on the weekends – so that sparked the interest. I ended up at Arizona State University, and by chance they had an aviation program. I remember I was flipping through a catalog thinking, “What am I going to do?” when I found out they had this program. It was in its infancy, so I went out and talked to the dean of the school. I think at the time, it gave me the exact kind of goal and purpose that I wanted and needed. I spent five years, part-time the last year, and then was a flight instructor. At the time when I left, the airline industry was going in the dumps – this was 2007 to 2008. Also, this was a time when I met my now-wife, Krissy, and the reality was sinking in about the realities of the airline career and l

ifestyle of a commercial pilot. I just no longer had the interest of traveling the country as a career. At the end of the day, it’s not unlike driving a bus. It just didn’t provide the same interest and stimulation as when I was learning to fly or teaching people.

You grew up in rural areas of southern Wyoming and Arizona. What do you see as some of the most important issues facing rural communities today?

I think the biggest issue I see is how the focus on the Front Range has become so significant. Politics, money, everything is focused on the Front Range. So as a result, you see communities being forgotten, water being diverted, and natural resources being depleted in these rural communities. The irony is that so many people move to Colorado because they value the rural areas. Yet the rural people who take care of these areas can’t live there. It’s really using the rural communities with little or no expectation of giving back.

Water is a painfully obvious example. Recently I went to a Colorado Open Lands event, where they talked about some of the impact that reallocating water from some of these rural communities has had on the landscape. The farmers needed cash, sold water rights, diverted upstream. Then water ends up not going to that area anymore. As a result, the land and the pastures previously devoted to farming or ranching are gone. And the previously beautiful area – where folks from Denver would want to go up and stay for the weekend – has been completely changed for the indefinite future.

Things like this, where the Foundation has a window of time to prevent change and protect landscapes and communities – we have a unique opportunity. We don’t want to look back at Colorado and say, “Gosh, I wish we could have gone out to Buena Vista or the Eastern Plains – small towns where you can stay and relax and do things – but now they’re lost to the monster of the Front Range.”

You have a young family, so this is a long way off, but – do you ever think about your own personal legacy? What’s most important to you, in terms of legacy – any specific causes you hope to positively impact, or a personal mission perhaps?

Going back to one of my initial comments – legacy to me means preserving what we currently have for the future. I can remember visiting Denver when I was younger, and in Arizona going up – you didn’t have the urban sprawl, or the impact on nature. If we can preserve what we have for future generations and allow them to make some decisions – that’s my hope, broadly, for a legacy. Colorado is at a turning point, where the population has exploded – and it’s not going to stop. I think about the financial crisis of 2008 to 2009, and now how the pandemic has reinforced the inequalities. Gosh, even people with high-paying jobs are struggling to live in Colorado and take care of their families. So that’s a big chunk of what I want to help preserve – and not only the physical environment, but also the educational opportunities and the financial mobility.

In a moment like this, when there is so much uncertainty and need in the community – and you’ve seen the Foundation act nimbly and be responsive to these needs during the COVID-19 pandemic – can you talk a bit about what that’s been like?

It’s interesting to think about where we are today. The Foundation is not small in terms of endowment, but by no means is it the biggest, and it will never be the biggest. So the nimbleness, the ability to adapt, and to use your resources in the best way is critically important for a foundation of our size. You look at how we operated the Foundation in the past – a Gates education center at the Zoo, the planetarium, the tennis center. At that time we were making these grants, Denver was smaller, driven by a smaller group of people. Now we’re at this point where the Foundation’s financial resources alone can never, on their own, make a serious change. So the ability to be flexible and change how we add value is now our greatest strength – not our balance sheet. It’s our ability to lead, and be strategic, and inspire others to join us. That’s a big priority for me as a board member – to help maintain that flexibility. I think it’s very interesting and appreciate the fact that the Foundation has shifted away from large grants to smaller – though we do have to be cautious of overextending. But at end of the day, $20,000 to a smaller organization or some rural community that desperately needs it – that can be more impactful than $20,000 gift to the zoo. So if we can drive change, and direct some of the staff efforts toward that type of community development – I think that’s really important.

Some other foundations have not adapted – they’re still really just a checkbook. You might see their name pop up on the TV or at the museum – but it makes you question whether that’s doing the best that they can. To me, this sets Gates Family Foundation apart – we’re willing to make change in a way that’s not the typical model. Nobody might have expected it, but I think we’re set up to make some real change in the world.

Finally, also in 2023 a total of $410,956 previously committed by Gates to the

Finally, also in 2023 a total of $410,956 previously committed by Gates to the

A total of $1,110,956 committed to the

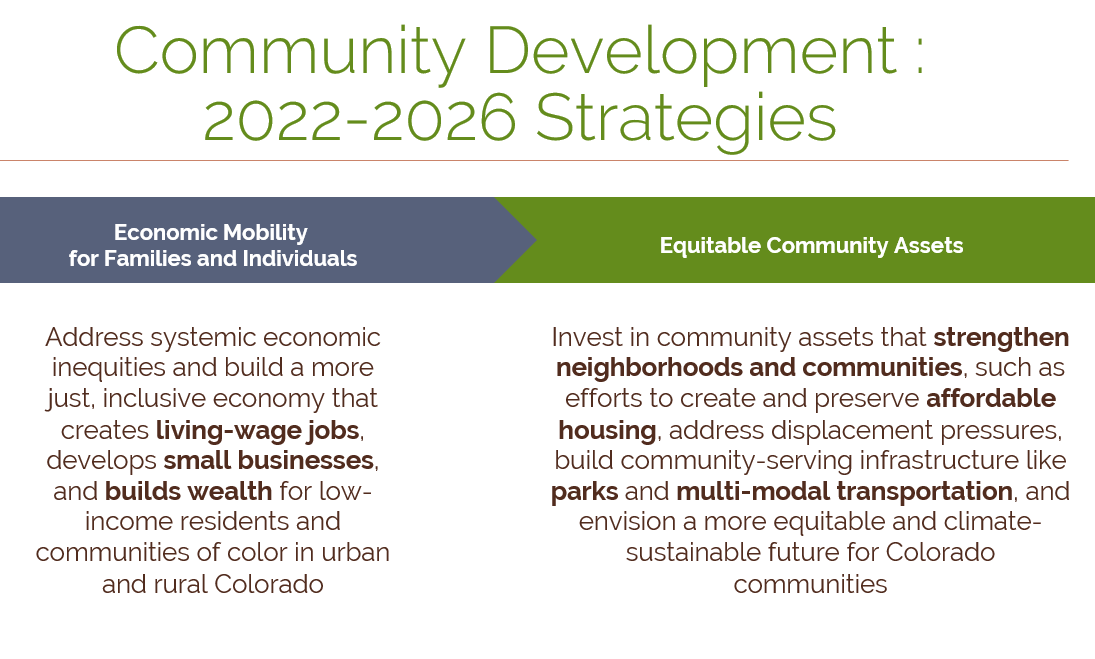

A total of $1,110,956 committed to the  In 2019, the Community Development program committed $932,500 in strategic grants to 13 organizations and $465,000 in responsive capital grants to 12 organizations. New impact investments supporting vibrant communities in 2019 included a $500,000 MRI to

In 2019, the Community Development program committed $932,500 in strategic grants to 13 organizations and $465,000 in responsive capital grants to 12 organizations. New impact investments supporting vibrant communities in 2019 included a $500,000 MRI to  Our Focus Landscapes initiative, a key element of our Natural Resources program, underwent a comprehensive review, revision, and re-launch in 2019. This initiative was launched in 2011 to help Colorado achieve landscape-scale conservation through the protection of private lands in specific geographies. A great deal of progress was made in North Park, southeast Colorado, and the San Luis Valley, resulting in more than 200,000 acres of farm and ranch lands conserved, along with their associated ecological values. The strategic review process was done in close partnership with the land trust organizations representing those geographies, providing lessons-learned and an exploration of emerging opportunities. The revised Focus Landscapes initiative will first focus on two geographies:

Our Focus Landscapes initiative, a key element of our Natural Resources program, underwent a comprehensive review, revision, and re-launch in 2019. This initiative was launched in 2011 to help Colorado achieve landscape-scale conservation through the protection of private lands in specific geographies. A great deal of progress was made in North Park, southeast Colorado, and the San Luis Valley, resulting in more than 200,000 acres of farm and ranch lands conserved, along with their associated ecological values. The strategic review process was done in close partnership with the land trust organizations representing those geographies, providing lessons-learned and an exploration of emerging opportunities. The revised Focus Landscapes initiative will first focus on two geographies: