“We need allies and support systems for our Native American communities. We need to ensure our partnerships are broad, and organizations like Gates Family Foundation can help elevate our voice.”

Ernest House Jr. joined the Gates Family Foundation board of trustees in January 2024. As former Executive Director for the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs (CCIA) for 12 years, Ernest maintained the communication between the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, the Ute Mountain Ute Indian Tribe, and other American Indian organizations, state agencies and affiliated groups. In that position, Ernest worked under former Governors Owens, Ritter, and Hickenlooper, and their Lieutenant Governors, along with the CCIA members to maintain a government-to-government relationship between the State of Colorado and tribal governments.

Ernest is a 2012 American Marshall Memorial Fellow, a 2013 Denver Business Journal 40 under 40 awardee, a 2015 President’s Award recipient from History Colorado, and a 2018 Gates Family Foundation – Harvard Public Leadership Fellow. In addition to his service on the Gates board, Ernest currently serves on the Fort Lewis College Board of Trustees, The Nature Conservancy Board of Trustees, National Western Center Authority Board, Conservation Colorado Board and the Colorado Interbasin Compact Committee. He is an enrolled member of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe in Towaoc, Colorado, and son of the late Ernest House, Sr., a long-time tribal leader for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and great-grandson of Chief Jack House, the last hereditary chief of the Tribe. His full biography is here: https://gatesfamilyfoundation.org/people/house-jr/

This spring, Ernest sat down with Melissa Milios Davis, Vice President of Strategic Communications and Informed Communities, for a conversation that ranged from the past to the present.

As the son, grandson and great-grandson of tribal leaders, how have your thoughts on leadership, community and representation changed over time?

I’ve been blessed to be born into leadership with my family. With that came a great responsibility to learn about the issues. I started accompanying my father to tribal meetings, learning about issues and traveling to Washington, D.C. when I was young. As a 10, 12 and 13-year-old kid, I wanted to go to the Air and Space Museum and eat freeze-dried ice cream. I’d get bored with the meetings. It wasn’t until I was 18-19 years old that it hit me. My father brought my grandfather along with us for one trip. We went to a water rights settlement meeting around Durango’s Animas-La Plata water project.

In his prepared comments, my dad made the case to Congress about how he’d been coming to D.C. to advocate for decades. He even accompanied his grandfather as an interpreter, discussing water rights issues years before. Now, as a tribal elected official, he was advocating for the same issues. He said I brought my son because I don’t want to keep doing this, but I’m prepared to pass this on to the next generation if he needs to be an advocate. For me, it was a big wake-up call. I realized how long he and other tribal leaders had been fighting for water, hunting, fishing and land rights. When I became Director of Indian Affairs for the State of Colorado, it all came back. I worked on hunting and fishing rights, water rights and natural resource issues. I was so appreciative that I learned firsthand about issues not in history books. These issues weren’t in college classes or any kind of program that I could learn or download. I had one of the best resources there to help and guide me through that process.

Throughout your career, you’ve served as a bridge between cultures. You’ve worked closely with numerous administrations at the state level. What accomplishments are you most proud of?

When I first started at the State, we were working on building awareness of tribal nations that have always called Colorado home and were forcibly removed over the last 150 years. Out of the 48 tribes, only two are still here – the Ute Mountain Tribe and the Southern Ute Indian Tribe. 46 other tribal nations were forcibly removed, some by gunpoint, to surrounding states. When I started in 2005, there was an effort to create a state protocol to recognize and respectfully return Native American human remains that were housed in History Colorado. In 2007, we became the first state to create such a protocol in partnership with tribes in Colorado and outside the state. A team led that effort, and they started long before I got to the state. Crossing the finish line with them was pretty powerful. It sent a strong message to tribal nations that weren’t working with Colorado that we were serious about our past, creating a dialogue and building a relationship.

I take great pride in being a bridge builder. I learned a lot of that from my father. Part of that has been figuring out ways that the state could build relationships around some of the most controversial issues like museums holding human remains without the consent of tribal nations. The federal government just created new rules for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Many museums across the United States have closed their exhibits down because they haven’t had adequate consultation with tribal nations. We started that and I learned from my predecessors who planted that seed. That’s one thing I’m proud of, which has put Colorado on the map.

Tell us a little about your role at the Keystone Policy Center. What do you do there, and what excites you most about your current work?

I love the Keystone Policy Center because it gave me an opportunity to continue working in challenging spaces and building bridges to find consensus. When I came to Keystone, I had the opportunity to launch the Center for Tribal and Indigenous Engagement. Now, I have a team that works on various issue areas, from education to natural resources to tribal consultation efforts. What it boils down to is helping folks build relationships with tribal nations. Our team does not speak on behalf of any tribes; we build the table, bring the folks that need to be there to the table, and let the tribes speak for themselves. We give them the platform they should have to talk about these issues. We walk away and start the next project, if we do our job well. The secret sauce of the Keystone Policy Center has always been engaging in difficult situations to find common ground. Anyone on my team will know I’m a big fan of collaboration happening at the speed of trust. When I think about those words, I think about tribes and how we’ve had so much mistrust for many years for many legitimate reasons. When we’re all seeking collaboration, we have to start from the beginning, which is something that Keystone has been able to give me.

Tell us more about the Kwiyagat Community Academy (KCA) project. What was this project, and why is it meaningful to the tribe?

I grew up attending the local school, as many of my fellow tribal members did. There was no school on the Ute Mountain Reservation before KCA was developed. There is a federally funded program called Head Start, but after that, K-12 students are bused off-reservation to the local community of Cortez. So, I’m a product of that. I remember hearing about my father, a product of the boarding school era. Not until later in his life did he share his experience – some good, some bad.

There was an ongoing conversation with tribal leaders I’ve worked with over the years about whether bringing a school to the Towaoc community would be beneficial. During COVID, however, everything changed. It was hard to move from in-person to online because email on the reservation is out for the day if the wind blows hard enough. Broadband isn’t readily available. Fiberoptic isn’t completely set up. So the structure had to be built and hotspots had to be put in. This got folks thinking that a school is something we need. The Gates Family Foundation’s support helped us build that structure while letting the tribe shape what it wanted the school to be. KCA focuses on the importance of language revitalization and cultural aspects that matter to Ute people. My tribal community is small – total enrollment is over 2,000 members; about 1,000 live within the community of Towaoc and 500 live in White Mesa on the Utah side. When things like COVID come, it’s scary because it could have completely wiped my tribe off the face of this earth.

As we thought about how to move forward, we thought that language revitalization, cultural awareness and education should be at the forefront, and that’s what KCA does. Kwiyagat means “bear” in Ute. Becoming the first charter school on tribal land was challenging, especially during COVID. Keystone Policy Center helped launch some of the efforts around the school. It started as K-2nd grade and has expanded to K-5th grade. Now, the tribe is thinking about how to go further and create an education campus— that covers K-12 and potentially higher ed.

You’ve been a trustee at Fort Lewis College. Why is an institution like that important?

This work has been so special to me. The history of the college was not something I knew about until I was working at the state. I learned that it started as a boarding school on the old campus in Hespers, Colorado, before it was transferred to where it is today. It began with a dark chapter when Ute, Navajo, Pueblo and Apache children were removed and sent there. Then, it closed down and became a school for farmers and their families in the area. Now, it is the university. Over 40% of our student body is Native, representing over 150 tribes on average for every incoming class. Many institutions nationwide have a Native American tuition waiver program, but Fort Lewis has had one for in-state and out-of-state Native Americans since the beginning. You can’t go anywhere in Indian Country – meaning the 574 federally recognized tribes and reservations across the United States, including Alaska – without somebody knowing or related to someone who went to Fort Lewis College. It’s that impactful to our Native American community nationwide.

The work around recognizing dark chapters, moving forward, and figuring out how to build community and support is really important. We did that this past year through state legislation and the boarding school report. We did a deeper dive into the cemetery, which potentially has Native American children who died at the boarding school on site. Those are hard questions and difficult conversations. How you move forward is key. It’s more than just this institution of learning. It’s also an opportunity to recognize these difficult chapters and figure out how to support the future of Native American education and scholars wherever they go. That’s one of the most important, impactful ways to turn around this dark legacy.

What do you think the responsibility is of an institution like Gates that is dedicated to benefitting the people of Colorado?

The organizations I’ve worked and aligned with have all been asking this question. It’s not an easy one, and there are no easy answers. This is hard work. What I’ve tried to do throughout my career is to uplift my community, my culture and my history. People often ask if I get tired of continually educating people on these issues. Doesn’t it get frustrating? I see it as an opportunity. Not everybody took that elective class, was part of a Native American community, or grew up in Colorado, so they don’t know this history.

When organizations like Gates recognize and acknowledge this history, it helps broaden our education. To fight this fight, we need allies and support systems for our Native American communities. If we just look at the numbers alone, the Native American population nationwide is 2% of the total population. It’s also 2% of the state’s population. That’s very small compared to states around us, like New Mexico and Arizona, where there are many more tribes, populations and land masses. We need to ensure our partnerships are broad, and organizations like Gates Family Foundation can help elevate our voices.

What are you most looking forward to in your role on the Gates board? What opportunity does working with the Foundation provide?

I’m excited to work with the team on the issues and projects they’ve been working on. I’ve spent a lot of my time thus far focused on some of the projects that are going on in my community, but I’m excited to learn more about the broader vision across the state. I look forward to learning from the folks who do great work and are invested in it. When you surround yourself with that community, it brings out the best in you. It revives and renews your efforts and interest in your own projects. That’s what I love about working with organizations like Gates Family Foundation. There are amazing leaders on the board and staff who I look forward to learning from.

What’s your favorite thing about Colorado? Favorite place to visit?

I’m always telling people the best part of the state is in the San Juan Mountains. It’s not just the cultural importance for me and my tribal community as Ute people. I still go back to areas where I grew up fishing and hunting. You can’t go wrong with the hiking, camping and general outdoor experience in the San Juans. My favorite place within my tribal community is the Ute Mountain Tribal Park at the back of Mesa Verde National Park. It was where my father was born. My dad took time away from being a tribal elected official for a while and became the director of the tribal park. I got to be a trail worker and a tour guide during that time. I still give tours and introduce folks to the area almost every year. I love introducing friends and family to the tribal park.

What else do you like to do in your spare time?

I love being home with my family. My wife is a counselor for Aurora Public Schools; she’s been doing that for 15+ years. My daughter Colbie is 14; she loves to swim and play soccer. My son Elijah is 12 and also loves soccer. Now, I’m just their driver. I love going from track meet to soccer meet to swim meet to something else. It gets my mind off everything and allows me to learn more about their lives.

# # #

Finally, also in 2023 a total of $410,956 previously committed by Gates to the

Finally, also in 2023 a total of $410,956 previously committed by Gates to the

A total of $1,110,956 committed to the

A total of $1,110,956 committed to the  In 2019, the Community Development program committed $932,500 in strategic grants to 13 organizations and $465,000 in responsive capital grants to 12 organizations. New impact investments supporting vibrant communities in 2019 included a $500,000 MRI to

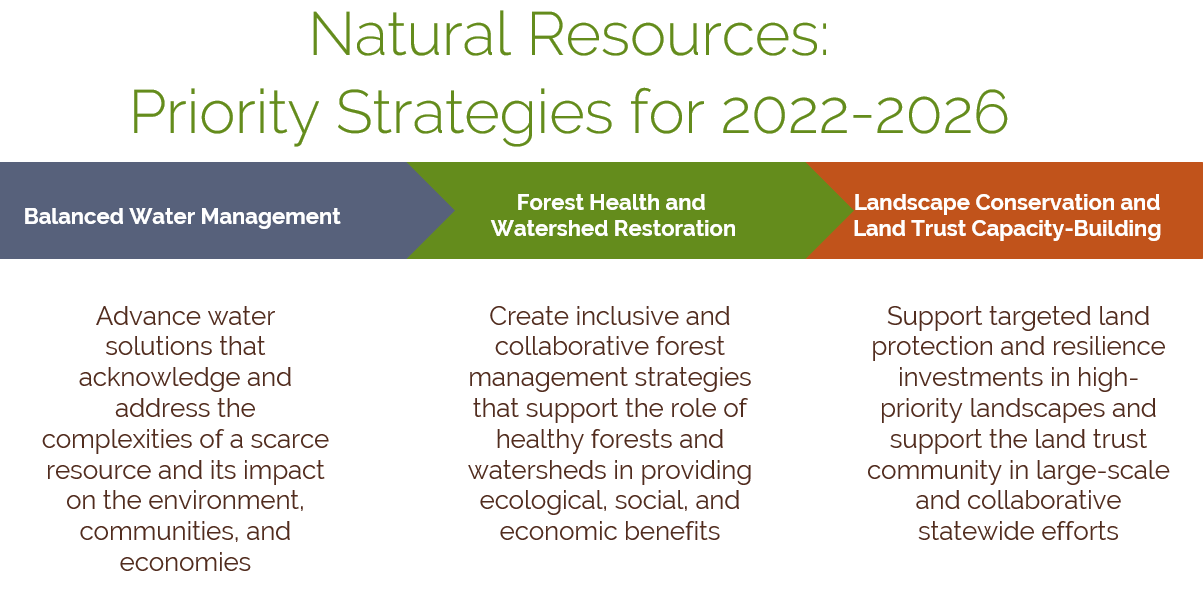

In 2019, the Community Development program committed $932,500 in strategic grants to 13 organizations and $465,000 in responsive capital grants to 12 organizations. New impact investments supporting vibrant communities in 2019 included a $500,000 MRI to  Our Focus Landscapes initiative, a key element of our Natural Resources program, underwent a comprehensive review, revision, and re-launch in 2019. This initiative was launched in 2011 to help Colorado achieve landscape-scale conservation through the protection of private lands in specific geographies. A great deal of progress was made in North Park, southeast Colorado, and the San Luis Valley, resulting in more than 200,000 acres of farm and ranch lands conserved, along with their associated ecological values. The strategic review process was done in close partnership with the land trust organizations representing those geographies, providing lessons-learned and an exploration of emerging opportunities. The revised Focus Landscapes initiative will first focus on two geographies:

Our Focus Landscapes initiative, a key element of our Natural Resources program, underwent a comprehensive review, revision, and re-launch in 2019. This initiative was launched in 2011 to help Colorado achieve landscape-scale conservation through the protection of private lands in specific geographies. A great deal of progress was made in North Park, southeast Colorado, and the San Luis Valley, resulting in more than 200,000 acres of farm and ranch lands conserved, along with their associated ecological values. The strategic review process was done in close partnership with the land trust organizations representing those geographies, providing lessons-learned and an exploration of emerging opportunities. The revised Focus Landscapes initiative will first focus on two geographies: